How to Make Any Process Work With Transactional NTFS: My First Step to Writing a Sandbox for Windows.

One of the modules in the Windows kernel provides support for combining a set of file operations into an entity known as a transaction. Just like in databases, these entities are isolated and atomic. You can make some changes to the file system that won’t be visible outside until you commit them. Or, as an alternative, you can always rollback everything. In any case, you act upon the group of operations as a whole. Precisely what needed to preserve consistency while installing software or updating our systems, right? If something goes wrong — the installer or even the whole system crashes — the transaction rolls back automatically.

From the very first time I saw an article about this incredible mechanism, I always wondered how the world would look like from the inside. And you know what? I just discovered a truly marvelous approach to force any process to operate within a predefined transaction, which this margin is too narrow to contain. Furthermore, most of the time, it does not even require administrative privileges.

Let’s then talk about Windows internals, try out a new tool, and answer one question: what does it have to do with sandboxes?

Repository

Those who want to start experimenting right away are welcome at the project’s page on GitHub: TransactionMaster.

Theory

Introduction of Transactional NTFS, also known as TxF, in Windows Vista was a revolutionary step toward sustaining system consistency and, therefore, stability. By exposing this functionality directly to the developers, Microsoft made it possible to dramatically simplify error handling in all of the components responsible for installing and updating software. The task of maintaining a backup plan for all possible file-system failures became a job of the OS itself, which started providing a full-featured ACID semantics on demand.

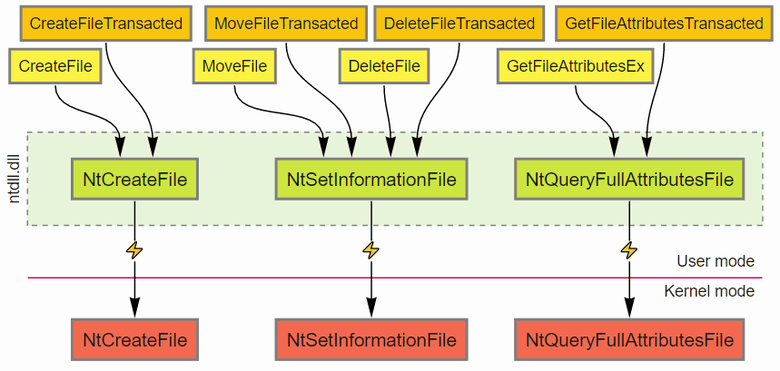

To provide this new instrument, Microsoft introduced a set of API functions that duplicated existing functionality, but within a context of transactions. The transaction itself became a new kernel object, alongside existing ones like files, processes, and synchronization primitives. In the simplest scenario, the application creates a new transaction using CreateTransaction, performs the required operations (CreateFileTransacted, MoveFileTransacted, DeleteFileTransacted, etc.), and then commits or rolls it back with CommitTransaction/RollbackTransaction.

Let’s take a look at the architecture of these new functions. We know, that the official API layer from libraries such as kernel32.dll does not invoke the kernel directly, but converts the parameters and forwards the call to ntdll.dll instead. Which then, issues a syscall. Surprisingly, there is no sign of any additional *-Transacted* functions on both the **ntdll** and kernel side of the call.

The definitions of these Native API functions haven’t changed in decades, so there is no extra parameter to specify a transaction. How does the kernel know which one to use then? The answer is simple yet promising: each thread has a designated field, where it stores a handle to the current transaction. This variable resides in a specific region of memory called TEB — Thread Environmental Block. As for other well-known fields located here as well, I can name the last error code and the thread ID.

Therefore, all functions with the -Transacted suffix set the current transaction field in TEB, call the corresponding non-transacted API, and restore the previous value. To achieve this goal, they use a pair of pretty straightforward routines called RtlGetCurrentTransaction/RtlSetCurrentTransaction from ntdll. They provide a sufficient level of abstraction, which comes in handy in the case of WoW64, more on that later.

What does it mean for us? By changing a variable in the memory, we can control, in a context of which transaction the process accesses the file system. There is no need to install any hooks or kernel-mode callbacks, all we need is to deliver the handle to the target process and modify a couple of bytes of memory per each thread. Sounds surprisingly easy, but the result must be astonishing!

Pitfalls

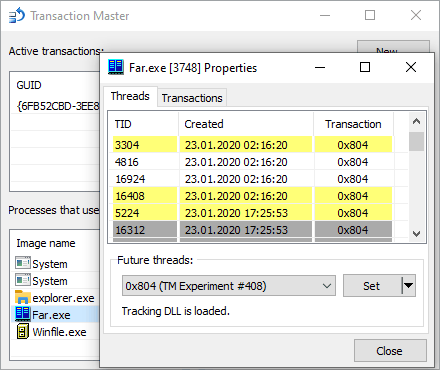

The first working concept revealed plenty of peculiar details. To my great delight, Far Manager, which I use as a replacement for Windows Explorer, is perfectly fine with transaction hot-switching. But I also spotted a couple of programs, on which my method didn’t have expected effect since they create new threads for file operations. An example of the second class representative is WinFile. Just as a reminder, the current transaction is a per-thread feature. Initially, it was a hole in the plot, since tracking thread creation out-of-process is quite hard, considering the time-sensitivity of this operation.

Thread-tracking DLL

Luckily, getting synchronous notifications about thread creation is extremely simple inside the context of the target process. All we need is to craft a DLL, that propagates the current transaction to new threads, the module loader from ntdll will handle the rest. Every time* a new thread arrives into the process, it will trigger our entry-point with the DLL_THREAD_ATTACH parameter. By implementing this functionality, I fixed compatibility with a whole bunch of different programs.

* Strictly speaking, this callback does not occur under every possible condition. Now and then, you will see one or two auxiliary threads hanging around without a transaction. Most of the time, these are the threads from the working pool of the module loader itself. The reason being, DLL notifications happen under the loader lock, which implies a variety of limitations, including the ability to load more modules. And that is indeed what such threads need to accomplish, parallelizing the file access in the meantime. Hence, an exception exists to prevent deadlocks: if the caller specifies the THREAD_CREATE_FLAGS_SKIP_THREAD_ATTACH flag while creating a thread with the help of NtCreateThreadEx, the DLL-notification callbacks don’t get triggered.

Starting Windows Explorer

Unfortunately, there are still some programs left that can’t handle transaction hot-switching well, and Windows Explorer is one of them. I can’t reliably diagnose the issue. It is a complex application that usually has a lot of handles opened, and if the context of a transaction invalidates some of them, it might result in a crash. Anyway, the universal solution to such problems is to make sure the process runs within a consistent context from the very first instruction it executes.

Thus, I implemented an option to perform DLL injection right away when creating a new process. And it turned out to be enough to fix crashing. Although, since Explorer intensively uses out-of-process COM, previewing, and some other features still don’t work on modified files.

What About WoW64?

The compatibility benefits that Windows-on-Windows 64-bit subsystem provides are sincerely remarkable. However, taking into account its specifics often becomes tedious during system programming. Previously I mentioned, that the behavior of Rtl[Get/Set]CurrentTransaction becomes a bit more intricate in this case. Since such processes work with a distinctive size of pointers than the rest of the system, each WoW64 thread maintains two TEBs associated with it: the OS itself expects it to have a 64-bit one, and the application requires a 32-bit one as well to work correctly. And even though, from the kernel’s perspective, the native TEB takes precedence, there is some extra code in these functions to ensure the corresponding values always match. Anyway, it’s essential to keep all these peculiarities in mind when implementing new functionality.

Unsolved Problems

As sad as it is, the first usage scenario that comes to our minds — installing applications in this mode — doesn’t work well for now. First of all, installers frequently create supplementary processes, and I haven’t implemented capturing child processes into the same transaction yet. I see multiple ways of doing so, but it might take a while. Another major problem arises when we try to execute binaries that get unpacked during the installation, and, hence, don’t exist anywhere else. Considering that NtCreateUserProcess and, therefore, CreateProcess, ignore the current transaction for some reason, solving this issue will probably require some creativity, combined with a bunch of sophisticated tricks. Of course, we can always rely on NtCreateProcessEx as a last resort, but fixing compatibility might become a nightmare in this case.

By the way, it reminds me of a story I read about a malware that managed to fool a couple of naïve antiviruses applying a similar approach. It used to drop a payload into a transaction, launch it, and roll back the changes to cover the tracks, enabling the process to execute without an image on the disk. Even if the logic of “no file — no threat” sounds silly, it might not have been the case for some AVs, at least a few years ago.

What’s With Sandboxing?

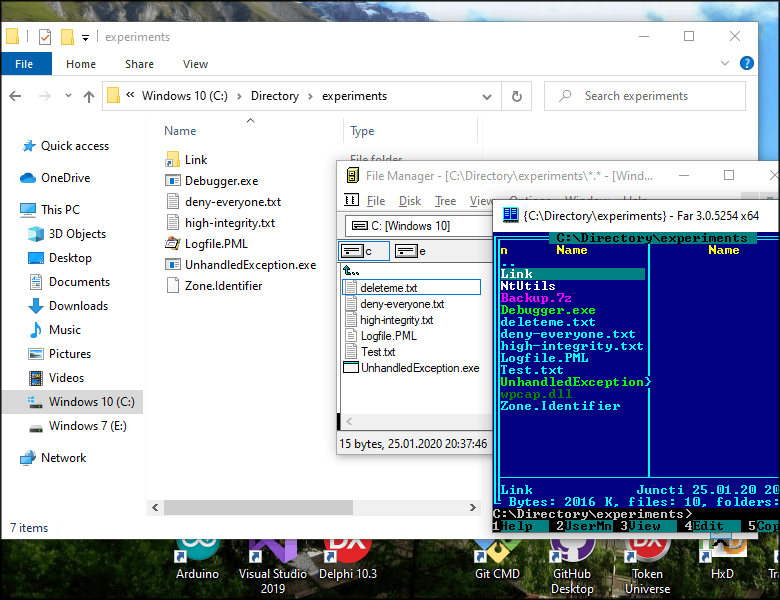

Take a look at this screenshot below. You can see three programs completely disagreeing on the content of the same folder. They all work inside of three different transactions. That’s the power of isolation in ACID semantics.

My program is not a sandbox whatsoever; it lacks one crucial piece — a security boundary. I know that some companies still manage to sell similar products, presenting them as real sandboxes, shame on them, what can I say. And you might think: How can you ever make it a sandbox, even being a debugger you can’t reliably prevent a process from modifying a variable that controls the transaction, it resides in its memory after all. Fair enough, that’s why I have to have another marvelous trick in my sleeve, which will eventually help me finish this project and which I won’t reveal for now. Yes, I am planning to create a completely user-mode sandbox with file system virtualization. In the meantime, use Sandboxie and keep experimenting with AppContainers. Stay tuned.

Project’s repository on GitHub: TransactionMaster.