Intercepting Program Startup on Windows and Trying to Not Mess Things Up.

Have you ever heard of Image File Execution Options (IFEO)? It is a registry key under HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE that controls things like Global Flags and Mitigation Policies on a per-process basis. One of its features that drew my attention is a mechanism designed to help developers debug multi-process applications. Imagine a scenario where some program creates a child process that crashes immediately. In case you cannot launch this child manually (that can happen for various reasons), you might have a hard time troubleshooting this problem. With IFEO, however, you can instruct the system to launch your favorite debugger right when it’s about to start this troublesome process. Then you can single-step through the code and figure what goes wrong. Sounds incredibly useful, right?

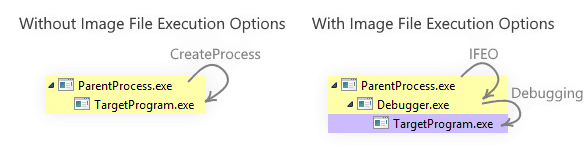

I don’t know about you, but I immediately saw this feature as a mechanism for executing arbitrary code when someone creates a new process. Even more importantly, it happens synchronously, i.e., the target won’t start unless we allow it. Internally, the system swaps the path to the image file with the debugger’s location, passing the former as a parameter. Therefore, it becomes the debugger’s responsibility to start the application and then attach itself to it.

So, are there any limitations on what we can do if we register ourselves as a debugger? Let’s push this opportunity to the limits and see what we can achieve.

Those who want to start experimenting right away can find the GitHub repository here.

I must say that it is not an innovative approach. I know at least three programs that utilize this mechanism for non-debugging purposes: widely known Process Explorer and Process Hacker — to replace Windows Task Manager, and AkelPad — to replace the Notepad. But we are planning to go way further.

Registering in IFEO

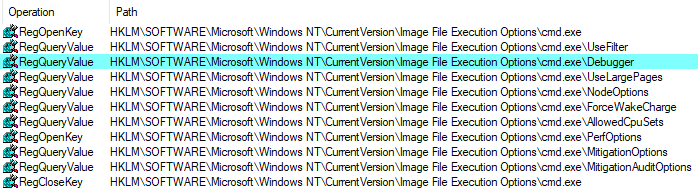

Looking at filesystem and registry activity while creating a new process reveals plenty of peculiarities. Besides filename corrections (which we will discuss a bit later), you can find how querying for IFEO settings works. Let us take a look at a portion of Process Monitor’s logs captured while I start cmd.exe.

As you can see, some code (located in kernelbase.dll according to the stack traces) checks various registry keys for existence. I highlighted the most promising entry that is supposed to contain a full path to the debugger and, optionally, its parameters. Therefore, here is an example registration:

[HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Image File Execution Options\TargetProgram.exe]

"Debugger" = "C:\Debugger.exe"

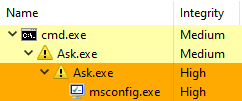

Looking at how the process trees compare, we can see where the debugger injects itself into the hierarchy:

It is worth pointing out the limitations:

- IFEO is a completely user-mode feature and has weaknesses similar to those of Software Restriction Policies.

- The operating system checks the sub-key for the image name only. Therefore, no masks are suitable. Sorry, but you cannot just intercept *.exe.

- Programs with identical filenames trigger the same action unless you use a specially designated UseFilter value, which allows you to set appropriate options based on the full path. Masks are also unacceptable here.

To enable a more granular distinction of files, create a non-zero DWORD UseFilter (as you saw in the captured registry access log above). If you do so, the system will enumerate all sub-keys (which can have arbitrary names), searching for the first one that contains a matching FilterFullPath value with a full path to the executable. Any settings specified in the matching sub-key will override the defaults (that apply as a fallback anyway). Note that sub-keys with missing FilterFullPath count as a match.

First Time’s (Never) a Charm

Alright, let us take a closer look at the prospects. We can intercept any program as it starts if we know its name and its face, provided we have enough access to the registry to set up our trap. It doesn’t matter who and how tries to launch it; they will end up calling us. Although knowing the image name in advance brings some limitations, it still sounds promising.

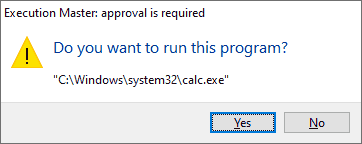

Being a middleware, we a free to decide whether we want to execute the target, and if so — how. When I first discovered this mechanism, my initial experiment was to write a tool that asks the user for consent whether they want to proceed. After a few minutes of research and programming, I wrote and registered an ultimately simple app with a Yes/No dialog that launches the intercepted executable if the user approves it. The first test spotted how naïve I was. Have you already guessed what happened when I pressed Yes? I saw the same dialog again. Repeatedly. Right, I fell into the trap I set up myself. It is going to be a long way.

I am not sure whether this mechanism would make any sense (at least for its original purpose) if it would not be possible for the debugger to start the target program anyway. Hence, yes, IFEO does have an exception. I was not entirely correct when I said it does not matter how you launch the application. As we know, Windows API provides several ways to start programs. The most well-known (and the ones we need) are ShellExecuteEx and CreateProcess. There are, in fact, more of them, although each one eventually ends up calling CreateProcess. The point is: all documented ways to create processes are aware of Image File Execution Options and follow their rules. The exception explicitly made for debuggers is that all programs started via CreateProcess with the DEBUG_PROCESS flag are not affected. It resolves the issue of entering an infinite loop of debuggers launching themselves but provides an additional argument why nobody should rely on this mechanism as a security measure.

Finalizing the Idea

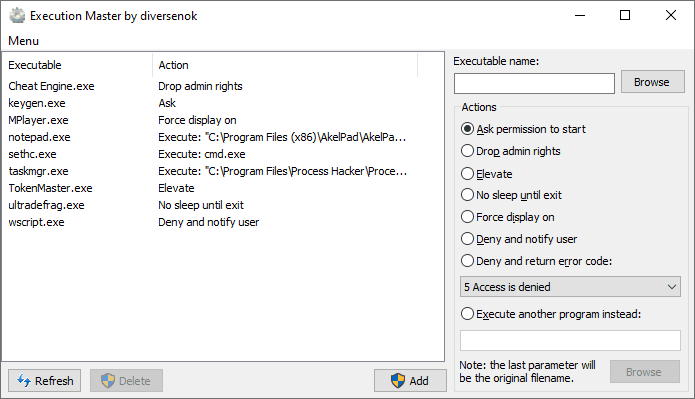

The original concept was to make an application that intercepts process creation and provides the user with a set of predefined actions. So, I came up with these small utilities:

- Ask.exe — notifies the user and requests a confirmation to proceed.

- Deny.exe — informs the user about unsuccessful attempts to launch a program.

- Elevate.exe — requests User Account Control for elevation and can be useful as a compatibility fix.

- Drop.exe — constrains access rights of the target process, so it appears to be running as a limited user. It works roughly similar to Michael Howard’s DropMyRights and Sysinternals’ PsExec (called with -ℓ key). Though IFEO certainly takes this feature to the next level.

- PowerRequest.exe — forces the system not to sleep or the display to stay on until the program exits.

I also wrote a pair of tools (a GUI and a command-line one) for registering these actions. You saw one of them on the screenshot at the beginning of the article. Their code is straightforward since they merely read from and write to the registry.

Making It Work

After all that said, we can finally proceed to the most exciting part: How to spoof an arbitrary process on the fly without messing things up for it. In theory, it sounds simple. There are several apparent steps we should take when re-launching the program after the interception. The process might depend on the inherited handles or the current directory, so we need to reproduce everything as precisely as possible. Which means:

- Passing the same command-line parameters.

- Using the same STARTUPINFO structure and the current directory.

- Letting the process inherit the same handles we did.

- Waiting for the target to exit and then exiting with the same code (to transfer it along the chain to the caller).

- And… another trick that I will explain a bit later.

Seems enough? Welcome to the world of pitfalls; we are just getting started.

One of the cunning questions you can try to answer right now is: How does the User Account Control react to all of our stunts? As a reminder, it is supposed to display the file’s location and verify its digital signature. What if someone registers an unsigned binary as a debugger for a signed executable? It might seem surprising, but UAC does not care. When you choose to run the target as an Administrator, its name will be in the consent dialog, and its digital signature will determine the visual design. The fact that the system launches a different executable does not change anything. Still, it is not a vulnerability since managing IFEO settings requires administrative-level access. Of course, there is a reasonable explanation for that, which I will reveal later. But in our case, it is perfect: everything looks as it is supposed to from the user’s perspective.

CreateProcess vs. ShellExecuteEx

As I already mentioned, these are two primary API endpoints for launching programs. CreateProcess is a lower-level function that provides more granular control over the new process, while ShellExecuteEx is a higher-level shell API that usually calls CreateProcess under the hood. They have overlapping functionality, but both provide unique behavior which can be useful under various circumstances. Here I highlighted the differences that are important for our storytelling:

- Since

CreateProcesshas an option to supply aDEBUG_PROCESSflag, it is the only (documented) way to bypass IFEO. - There is a specific class of executables that requires administrative privileges to run. A call to

CreateProcessmade by an unprivileged user on such a file might fail withERROR_ELEVATION_REQUIRED. The only way to proceed in this case would be to useShellExecuteExwith the runas verb. We will discuss how this verb works later. ShellExecuteExrequires the caller to supply the filename separately from the parameters, whileCreateProcesscan work in both modes.

Breaking the Loop

The previous list confirms that using any single one of these functions would not suffice our needs. We must bypass IFEO, but we also want to start programs that run only as an Administrator, even from an unprivileged user. There is, of course, a widely-used solution on how to handle elevation:

if (!CreateProcess(…))

if (GetLastError() == ERROR_ELEVATION_REQUIRED)

ShellExecuteEx(…); // using "runas" verb which triggers UAC approval dialog

We first try to use CreateProcess, and if it does not work, we ask the User Account Control (and, therefore, the interactive user) for help and elevation. So, after getting ERROR_ELEVATION_REQUIRED, we are left with no choice but to use ShellExecuteEx, which… always launches our debugger and not the target! Fortunately, the second instance will have administrative rights and would not have trouble breaking through IFEO using CreateProcess. We just fell into our trap, cloned ourselves, and recovered. Thus, we need to include additional logic to suppress duplicate interaction with the user because we do not want to ask them the same questions twice. How could you ever think of anything like that in advance?!

Where Are All My Parameters?

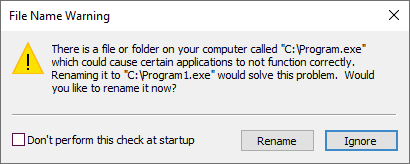

Addressing the third issue on the list: this is something people do not notice because it just works. Well, at least most of the time. When calling CreateProcess, you can provide the entire command-line as a single string. The function will automatically determine which part stands for the filename, interpreting the rest as the arguments. The documentation emphasizes that if the filename contains spaces, the calling code should wrap it into quotation marks to separate from the parameters. Otherwise, it becomes ambiguous and can lead to vulnerabilities through misinterpretation. The same applies to the outdated WinExec function, which is merely a wrapper over CreateProcess. Unfortunately, programmers tend to ignore this part; perhaps, because the correction logic embedded into CreateProcess is surprisingly good at guessing.

When someone attempts to start the target, we receive the intended command-line as-is. Therefore, if the parent happened to ignore the quotation rules, it might be unclear which program to execute. Let me illustrate how CreateProcess deals with these scenarios. Assuming we pass it C:\Program Files\Some Folder\Program Name -parameter, it starts guessing by splitting the string on each space (additionally substituting .exe since it is an optional part of the input), checking files for existence:

C:\Program Files\Some Folder\Program Name -parameter

C:\Program.exe Files\Some Folder\Program Name -parameter

C:\Program Files\Some Folder\Program Name -parameter

C:\Program Files\Some.exe Folder\Program Name -parameter

C:\Program Files\Some Folder\Program Name -parameter

C:\Program Files\Some Folder\Program.exe Name -parameter

C:\Program Files\Some Folder\Program Name -parameter

C:\Program Files\Some Folder\Program Name.exe -parameter

C:\Program Files\Some Folder\Program Name -parameter

C:\Program Files\Some Folder\Program Name -parameter.exe

I highlighted the filename part in bold; the rest contains the arguments. If none of these files exist, the function fails; otherwise, it uses the first match. As an experiment, you can create a file called C:\Program.exe to see if any application on your computer has this bug. Interestingly, Microsoft even made Explorer show a warning if it finds this file on startup.

As for our tools, in some cases, we might have no choice but to use ShellExecuteEx, which does not include any correction logic and forces us to supply both parts individually. Therefore, we should mimic CreateProcess’s behavior and try to guess what other programs want to achieve.

Stop Debugging Me

I mentioned it several times already: if you need to bypass IFEO, use the DEBUG_PROCESS flag. The reality, however, is a bit more intricate. As part of its main functionality, this flag initiates a new debugging session that, in turn, subscribes us to all sorts of notifications about the target. They include exceptions, process and thread creation, module loading, and so on. Since debugging is a synchronous operation by nature, the new process won’t have a chance to execute anything unless we acknowledge it by responding to these notifications. Simply adding this flag to an existing code makes the new process appear to get stuck immediately.

Therefore, we have two options — we should either carefully respond to everything we receive or explicitly opt-out of debugging altogether. The first approach implies a loop of WaitForDebugEvent plus ContinueDebugEvent and seems less reliable for our purposes. The second option allows us to proceed as usual after calling DebugActiveProcessStop. Though, the last function can fail under some circumstances since it re-opens the target process by PID. A better way is to use NtRemoveProcessDebug.

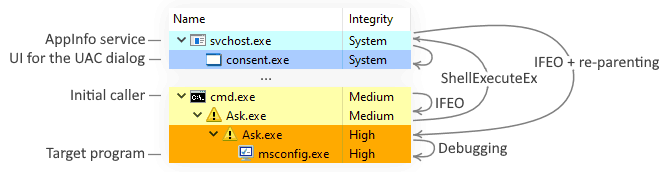

The Magic of AppInfo

As I said before, User Account Control does not seem to interfere or even notice that we intercept process creation. At this point, you should have all the necessary pieces to answer why. When a program with insufficient permissions needs to run something as an Administrator, it uses ShellExecuteEx. Still, there is a security boundary on its way, so we need a privileged component to create a process on our behalf. What function is it going to call? CreateProcess, indeed.

Here is how it goes: a program calls to ShellExecuteEx specifying the target filename. Under the hood, this function uses COM/RPC to forward its parameters to the AppInfo service that handles elevation requests. This service starts consent.exe, which, in turn, validates the digital signature of the target file and displays the famous UAC dialog. After the user approves the elevation, AppInfo calls CreateProcessAsUser, which internally checks for IFEO and swaps the target filename. So there we have it: UAC is clueless about what is happening!

There is also another peculiar topic I want to discuss in this section. Every process stores an identifier of its parent, and some tools use this field to display processes in a tree-like hierarchy. Surprisingly, when it comes to elevation, the caller of ShellExecuteEx still appears as a parent, even though svchost.exe does all the work on its behalf. How is it possible? Yet, even better, can we achieve the same? When we set up the interception, we instruct the system to inject our debugger into the hierarchy, essentially gaining control over the subtree. It is perfectly normal unless we deal with a multi-process application that depends on correct parent-child relationships. In this case, we should re-parent the new process the same way AppInfo does. Luckily for us, this option is documented: all we need is to use PROC_THREAD_ATTRIBUTE_PARENT_PROCESS and STARTUPINFOEX. We can use this trick to improve compatibility: the target program would not even know what happened.

By the way, altering the hierarchy does not require any privileges, only

PROCESS_CREATE_PROCESSright (part of write access mask) on the new parent, so the process tree might not be as reliable for determining who ran what as it seems. Moreover, it is possible to attach a child to an already exited process, as long as you have a handle with sufficient permissions.

Bonus Section

Here are some funny miscellaneous questions about the topic.

Q: Let’s say you assigned B as a debugger for A and then set C as a debugger for B. What happens when you run A?

A:CreateProcesschecks for IFEO, encounters an entry for A that points to the debugger B. It swaps the target filename and restarts processing. Then it checks IFEO for B and discovers C. As a result, starting A launches C.

Q: Okay, but what if we set a program as a debugger for itself?

A: The same logic applies: we restart the processing every time we encounter an IFEO entry for the file we are about to execute. Will the function hang indefinitely because of that? Fortunately, not. The debugger always receives the intended command line as a parameter, so swapping the filename also expands the list of parameters with the former image name. It is equivalent to prepending the command-line with the content of the Debugger field from the registry key. Since the system limits its maximum length by 32,767 characters, the process stops eventually.

Q: How about specifying a non-executable file as a target? Or even a string that doesn’t represent a valid filename?

A: Then, of course,CreateProcessfails. The specific error code depends on the provided string and can be both peculiar and misleading. Just imagine a program that collects telemetry about its failed attempts to update itself that fail with “This file is not a Win32 application” on something that certainly is. Can you imagine the amount of troubleshooting it’s going to take to figure out that the client was playing with IFEO and forgot to disable it? Here is a set of errors I managed to get:

ERROR_FILE_NOT_FOUNDandERROR_PATH_NOT_FOUND— specifying a non-existent file or a path that is too long to be valid.ERROR_ACCESS_DENIEDandERROR_SHARING_VIOLATION— point to a file that you cannot access due to protection or locking.ERROR_INSUFFICIENT_BUFFER— recursive debugging from the previous question.ERROR_CHILD_NOT_COMPLETEaka “Application cannot be run in Win32 mode” — a native executable or a driver.ERROR_BAD_EXE_FORMATandERROR_EXE_MACHINE_TYPE_MISMATCH0xFFFFFFFE(only forShellExecuteEx) — a file with a Zone Identifier set to 4 (restricted).

Conclusion

Exploring Image File Execution Options and crafting a tool on top of it turned out to be surprisingly fun. I hope you enjoyed reading about it the same way I enjoyed discovering and addressing neat pitfalls and weird peculiarities arising in the process.

You can find the tool and its sources on GitHub: ExecutionMaster

As a last note, remember that IFEO has a machine-wide scope because it resides in the HKLM hive. Hence, the adjustments you make have an immediate impact on all users, including NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM, and, therefore, can partially affect the operating system. My tool shows warnings when you try to configure interception for a well-known OS component and also suppresses UI dialogues in the zero session, but keep that in mind.